Handel blog 3*

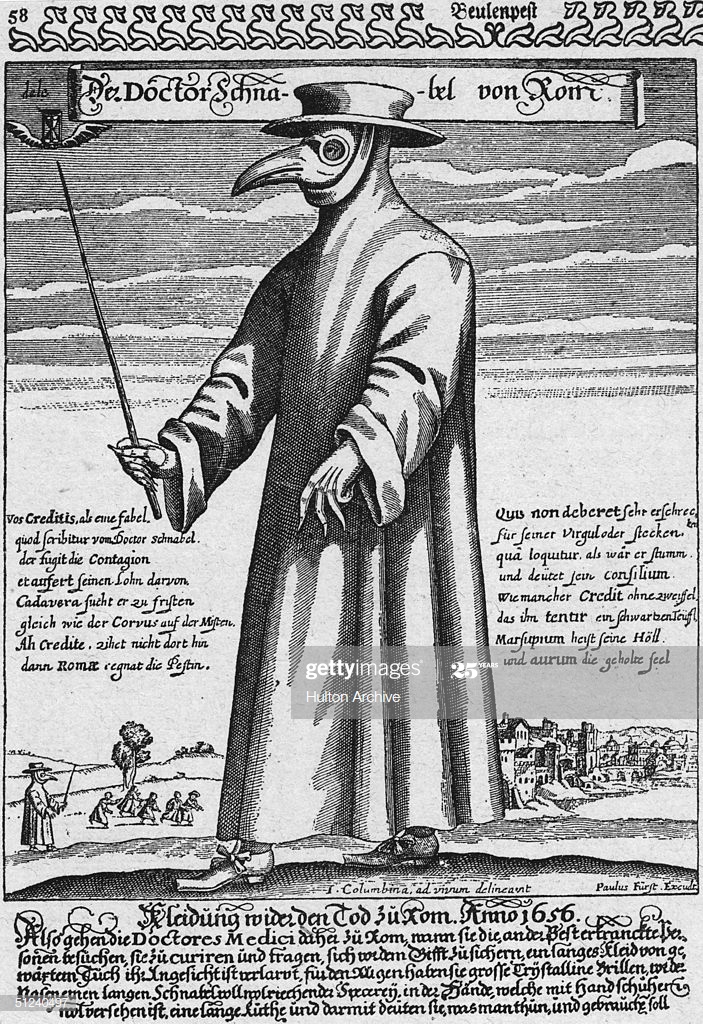

From Katherine: Well, we talked about the Plague song “O du lieber Augustin” last time. I’ve seen quite a few songs popping up on social media—either parodies that reference the coronavirus or sometimes simply old songs meant to distract us from our worries. But today I wanted to bring together comments some of you have made about masks—the surgical masks now in such demand in so many public contexts. I’ve seen several articles commenting on the beak-like “doctors’ masks” that were seen as a symbol of the Plague in the early 1700s. The “doctor’s mask” was even used as a clue in the 2017 Disney movie Beauty and the Beast—a sign that Belle’s mother had died of the plague. I expect the Handel-era doctor’s mask served a different purpose than the surgical masks we have today. What do you think?

From Rebecca: Masks have been connected with healing in cultures throughout the world—think of the stereotypical witch doctor wearing a colorful mask. But there are much more serious meanings associated with the use of masks. I find it interesting to hear some of the beliefs about the wearing of protective masks today. And there is even a kind of folk craft springing up—people making their own masks or producing some to help out with the shocking shortage of face masks here in the US. You can read about some of the information on making masks here.

From Peter: I did a little research on the doctor’s mask we associate with the Great Plague. By the time Handel was living in London, from the early to mid-1700s, the beak-like doctor’s mask had fallen out of use, but interestingly some of the reasons for its emergence in the first place remained a part of the culture. It seems the beak protuberance part of the mask was actually filled with various herbs or spices that supposedly protected the wearer from illness—well, THE illness, the plague. I assume the spices did at least smell better then whatever the doctor was encountering where ever he went. Anyway, along with that tie to the mask itself, there was also a general belief among physicians and their patients that certain smells carried medical benefits. What we think of as perfumes today were regarded as a kind of medicine back then. One article I read said this about such cures in the 1700s: “Recipes in pharmacopoeias confirm that physicians believed in the medicinal properties of perfumes.” You can read about it here.

From Katherine: That is fascinating, Peter. It brings to mind the more modern practice of aromatherapy with its use of essential oils. You can read about aromatherapy here. But it also made me think of Handel and one of the last people who saw him before he died—his friend and neighbor James Smyth (see p. 57 in The Handel Letters). James Paul Smyth was a perfumer. My guess is that he was there as both a comfort and a kind of Hospice health care worker, bringing the oils and perfumes that represented this medicinal part of his trade. Handel was clearly grateful for Smyth’s services. He left James Smyth a substantial bequest in his will.

I think that is it for today. Stay well.

*All posts listed as “Handel blog” are texts that use the fictional characters in my book The Handel Letters: A Biographical Conversation. As in that book, the posts will often reference things from Handel’s life or time period as starting points. And the post will cite a page or paragraph in the book when it seems relevant. Find The Handel Letters.