Handel blog 6*

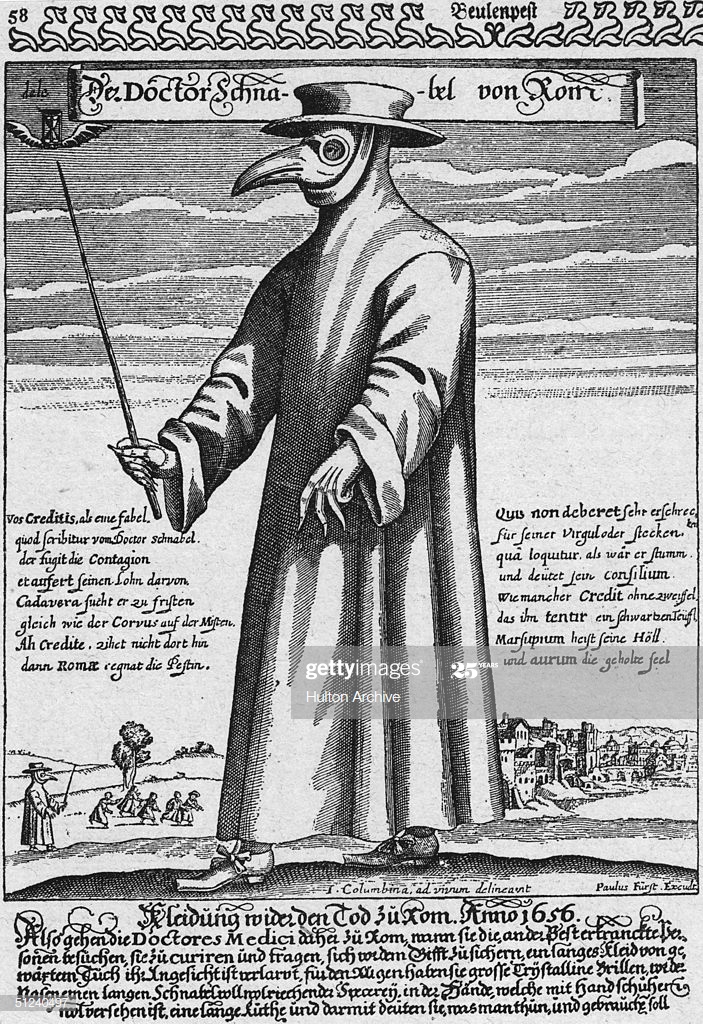

From Katherine: If you watch television, some sources say do wear a mask. Others say it is unnecessary, just a recommendation. Some say find that malaria medicine; it will cure the virus. Doctors say nothing has been proven to work against COVID-19. Some news sources say things are starting to turn around. Others say the worst is yet to come. How do you know which sources to trust? How did people get accurate news stories in Handel’s day? Journals, letters, and newspapers were a lot slower than today’s television, Internet, and other media. Notwithstanding their slowness, were eighteenth-century sources more accurate? Could you trust them?

Defoe’s Journal of the Plague Year was written in 1722, 57 years after the Great Plague of London in 1665. Critics still debate over what to call Defoe’s work. Is it history, historical fiction, a novel? In our discussions of Lydia’s letters to Handel, we, too, wondered about the source of one story she mentioned—a piece of news that reached London before Handel had returned from a 1750 trip to the continent. There had evidently been a carriage accident near Harlem in the Netherlands in which Handel was injured. Peter commented: “Actually, as Brad suggested, it was odd that this incident was reported among Handel’s friends in London. Obviously Handel himself was not the one sharing the information, maybe a newspaper story instead.” (p. 478) How did people in London know? Was it a rumor? What did they know? Handel’s friends must have wondered and worried as they had only vague secondary sources on the incident until Handel himself came home and set the story straight.

From Ross: I don’t know much about it, but I know there is a source people can use today to help them decide whether the news we hear is reliable. In Handel’s day, the sources were fairly limited, but today there are countless sources of varying quality. You can get an app called Newsguard that is supposed to give an evaluation of news sources derived through a set of criteria and applied by professional journalists. The idea is simply to give a grade to the source itself, not to dissect any given news item.

From Angela: Forella wanted me to mention that we have been watching one of those Great Courses Plus series of lectures, this one titled Fighting Misinformation. So far, it has been pretty interesting, and I think they did mention that Newsguard app as well.

From Clara: Well, this is all very interesting, but I was expecting someone to comment on the movie about Farinelli, but since we haven’t moved in that direction, let me suggest a movie you should all watch while you are sheltering in place. It’s Teacher’s Pet—the 1958 version with Clark Gable and Doris Day, not the newer one. It’s about journalism, and to me anyway, what we are really trying to grapple with here is a major change in journalism from earlier times. Watch the movie and let me know what you think. You can read some info on it here.

From Katherine: Thanks Clara. Teacher’s Pet is one of my favorite movies, and you are right. It raises many questions about the role of journalism then and now. A good suggestion for something to watch this evening. Stay safe, everyone.

*All posts listed as “Handel blog” are texts that use the fictional characters in my book The Handel Letters: A Biographical Conversation. As in that book, the posts will often reference things from Handel’s life or time period as starting points. And the post will cite a page or paragraph in the book when it seems relevant. Find The Handel Letters.